His Name’s Not Bambi

Living with cancer is better than living with nothing, as in not living or being blank conjecture. I haven’t had a thought in a month, so I haven’t had a feeling about a thought and that means there’s been nothing to say. So I said it. But I’ve started to import them – feelings – now much more consciously than the drip, drip, drip or the dot, dot, dot that snuck up from somewhere over Xmas when I became dependent on historical dramas and period costume drama-documentaries and I caught myself with a voice in my head as I looked online at the TV listings that was wondering to myself “Are any of My Programmes on tonight”. As if I AM this kind of nothing too. Anyway, these programmes taught me that having babies should override not only personal happiness but also the prevention of abuse or the refraining from self-abuse.

Living with cancer is better than living with nothing, as in not living or being blank conjecture. I haven’t had a thought in a month, so I haven’t had a feeling about a thought and that means there’s been nothing to say. So I said it. But I’ve started to import them – feelings – now much more consciously than the drip, drip, drip or the dot, dot, dot that snuck up from somewhere over Xmas when I became dependent on historical dramas and period costume drama-documentaries and I caught myself with a voice in my head as I looked online at the TV listings that was wondering to myself “Are any of My Programmes on tonight”. As if I AM this kind of nothing too. Anyway, these programmes taught me that having babies should override not only personal happiness but also the prevention of abuse or the refraining from self-abuse.

And I found out that Queen Victoria thought breastfeeding was disgusting. Personally, I like it, but it’s hardly my place or the point: her breasts were Albert’s alone. When her daughters had babies and showed them physical affection and did breastfeeding Victoria was so disgusted that she named a cow in one of the royal herds after one of them, HRH udders, cow Princess Alice.

What I did lately, when things got really rock bottom empty of any emotion was go and see Les Misérables. I cried at the right parts, would give the Oscar to Anne Hathaway and what the film took 3 hours to teach me is that so long as we believe in God it is totally OK to own women (a woman) in whatever way you like and that wealth is redemption. Obviously I feel better about myself for all this guidance and inch back to language.

Right.

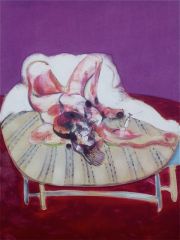

Finishing chemotherapy is a bit like being dumped. You don’t finish it, it is finished for you by someone else. Pricked, questioned, proven, known, told, made OK, not OK, listened to, limited, fearless, terrified, numbered it was like the flesh nailed to the bed

and then not when it is scheduled to be, it’s over, which you’d think could be a good thing – like, a relief – but it isn’t because I’m back to pure conjecture, as above, which is an empty space. And no voice. Somebody else is looking at pictures, not me. I am waiting for more, stuck and blind. Not that they should, but no-one gives me my body back. It is left. To self-diagnosis, everyday – as in ordinary or familiar, and frequent. There is a line rubbed out, which means there is nothing to resist, no grip but this and this only now: the clutching at some scatter and I cannot breathe.

and then not when it is scheduled to be, it’s over, which you’d think could be a good thing – like, a relief – but it isn’t because I’m back to pure conjecture, as above, which is an empty space. And no voice. Somebody else is looking at pictures, not me. I am waiting for more, stuck and blind. Not that they should, but no-one gives me my body back. It is left. To self-diagnosis, everyday – as in ordinary or familiar, and frequent. There is a line rubbed out, which means there is nothing to resist, no grip but this and this only now: the clutching at some scatter and I cannot breathe.

But let’s move on.

I say we go on, but do we? Fiction is not sustaining. By definition, fiction is not sustainable. But I drag myself into this because I know it’s exemplary, and necessary:

I’ve seen Bambi L. twice since I last wrote and we’ve been waiting for him via these others, but that was so long ago that he’s only on the edge of existing, though that isn’t the only reason.

The first time it was still figure-to-figure, so to speak. I wonder what I can remember, or be bothered to. This storytelling… I know I’d thought about what to wear and so had he and he disappointed me with properness – grey and blue, city boy shirt with a white collar and matching black socks. Matching black socks. Matching black socks. What an affront – that nonetheless made me feel less guilty at my own Sadism in having chosen, deliberately but without any real reason – which is perhaps its very definition – my t-shirt with the diagonal stripes that can make the looker-on feel a bit sick (well, myself too, if I look down). Clean pants this time. I don’t know why. I don’t know why, but it was as if we might have been asking for it: distance. Tzzzz. We were holding ourselves up, and separately as if there was something behind each of us.

Well. Proper was as proper did. Like an upright manboy he re-presented every factual thing I’d told him in absolutely precise detail: from my description of lymphoma to the number of brothers and sisters my mum has. Wanting to give a bit of hard flash back I gave a speech about the irony of ‘progressive’ hospital architecture housing an archaic, patriarchal professional hierarchy. Which was because of a consultation I’d had with a doctor who was so totally hopeless at communicating that he should go back to school. I’d even take him if I had the time. In general, what a doctor can be bothered to say to a patient diminishes with seniority, in inverse proportion to their sense of entitlement – to waves parting, doors opening, never having to be so low as to have to stick a needle in anywhere, to a golf course at the end of their garden, a yacht, the villa, helipad, Hampstead whatever. It’s absolutely enshrined this sense of entitlement no matter how much of an atrium they sit you in with however many choices of chairs and foot stools and potted plants and nurses called Carey to be plugged with chemotherapy. It’s a neo-liberal smear, this architecture, and it works and I did not mind that it did. I was glad of it. But moreover, this sense of entitlement that senior doctors have, the ones they call professors sometimes, is systemic. Of course you want to be edified by these dead things given what you’ve gone through to get there, they match the life given up, the extremity of the sacrifice, the close-to-the-edgeness of what’s humanly possible, the tiredness. All that.

And as I’m riffing on this Bambi stops scratching his pen on his pad and he’s standing and just stares and his mouth slowly slowly opens which makes more words come out of mine in a steady flow and his is smiling without curling upwards, by which I mean I know it’s recognised and I feel like a soothsayer in a marketplace and I think when I got to the end he might have just said something like “How do you know these things?” And I tell him I think about them; I’m all a bit pleased like this thing is there now, projected. And he tells me he’s going to an interview for a student research post, which posts are highly competitive. And how he’s chosen his number one project he wants to get onto which is a cancer project because he was so inspired, etc. We went through the questions he might expect but it turned out the interviewers mainly asked him about a recent debating society argument on women and offered him a coveted place on something to do with microscopes, which he also loves… I don’t mean to sound cheap, but I bet he’d have found my neutrophils on new year’s eve. But stop. Have I gone too far?

The first visit ended with him leaving before me but not before he told me he aspired to become a surgeon. And there, friends, is where I found my punctum. By which I mean it really lingered on my mind like an anomaly and a gnarl, a knot. It didn’t seem so strange but for its lingering. And what I came to think was a question about whether saying this, having this aspiration was also about making a lifestyle choice. Like you can’t really take any drugs. No disco dancing. No mess. It’s like being a pilot. Tip top of the tree of this endemic, systemic self-perpetuating sacrifice/entitlement regime. The power. I thought about a conductor who once gave Andrew and I a lift home in his car from the opera and how he was the only man I ever saw wearing driving gloves to drive. And it lodged with me – to be a surgeon… – and grew and I tried it out on some friends until I started to round on a question for Bambi.

And I asked this question quite near the beginning of our second meeting since the last time I wrote – I’ve never been one for cards close to chests. Even in this same meeting, but later, we were already reminiscing and I told him about his odd socks the first time we met and knew after that I should never expect him to wear odd socks ever again. It was just before Christmas and carol singers had turned up and subjected everyone pinned down with poison which was absolutely an abuse and I railed against them and we laughed quite a lot and swapped what we hate and we had a long wait before the chemo process even began and I apologised and he said he didn’t care, he didn’t come for that, he came to see me, and really to laugh because he said I was hysterical. And tough as nails. Tough as nails. He liked saying that. I think it gave him an image of killing cancer cells that made him feel good, this happy bunny saviourboy.

But I told him, I said, that I’d been wondering whether choosing to become a surgeon was also a lifestyle choice. And he said it was and now he looked a bit pleased and said it meant you married a nurse (as in a man and a woman) (there were other things too, but I forget) and then I said: And have you made that lifestyle choice? Really carefully, not toying. And he leaned back in his chair and let out a soft noise from his throat, like how men do when they are easing into position and he said that he would be the exception. And you know what? That’s when the punctum snapped. I snapped the punctum.

What evolved over the next four hours as Jane dripped me stripped him of fictions, of this figuring and I can’t go on. I’ve not minded the liberties I might have taken with the ethics of him as a public, but any more and he wouldn’t be one even if I am still to him: I’d be telling you about the private life of this person and it is not mine, it’s walled-off from this. He knows things about me that no-one else knows and he will write these things in his report. I know things about him that probably quite a few people who know him already know – I mean it’s no big news if a person was an organ scholar is it? – and yet it’s not OK to report them. Even though I am quite sure that I am no more real here than he is. I told him about how I lived, my thoughts about sexual fidelity and he liked them without application.

And you know what? The story has snapped. He isn’t a story any more. Full. Stopped. Fiction is not sustaining nor sustainable. It leaks out, dribbles away, dries up like words. By which I mean I have not seen him since and that his name’s not Bambi, it is Luke.

Next stop, The Heart Hospital. No joke. Frankly that fiction is sustaining is so much its biggest lie that we already knew that it’s nothing more than a joke. Information, on the other hand: I will find it.

Next stop, The Heart Hospital. No joke. Frankly that fiction is sustaining is so much its biggest lie that we already knew that it’s nothing more than a joke. Information, on the other hand: I will find it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.